This is a Forbes article by William Baldwin which I found to be extremely helpful and easy to follow. I also agree with his advice….

Some assets are terrific holdings in estates. Go to your grave clutching them.

Some are bad for heirs. Play hot potato with them during your senior years.

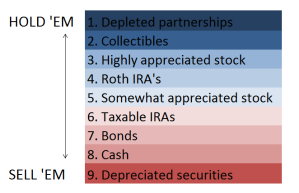

What follows is a tax ranking for retirement assets. At the top: the holdings you should hang onto as long as you can. At the bottom: the holdings that you should be most inclined to cash in when you need to pay the rent.

Key assumption: You have more than enough savings to live on, so it’s likely you will be leaving something to children and grandchildren. Your objective is to keep your family’s tax burden as light as possible.

The important element of the tax code that drives our ranking is called “step-up.” Appreciated assets left in your estate get stepped up in tax basis when you die, with the appreciation never taxed. If you buy a Google share for $100, hold on for more than a year and die when it’s worth $1,000, then neither you nor your heirs will owe income tax on the $900 capital gain. If they sell two months later for $1,015, their gain is $15.

The main focus here will be on income taxes owed by either you or your descendants. Inheritance taxes, for most families, are far less important. The federal estate tax applies only to larger estates ($10.6 million, if held by a married couple), and a lot of states don’t tax estates.

Most of the choices described below won’t affect estate taxes. In the Google example, the share goes on an estate tax return at its $1,000 market value. Roth and other IRAs are subject to the estate tax.

My ranking is based, in large part, on a white paper put out a year ago by AllianceBernstein. The experts at this firm are wealth managers, not tax attorneys, but their investment advice is very tax-wise. They won’t be doing your tax return but they might be telling you why, for tax reasons, you should hold onto that master limited partnership they put in your portfolio.

Here’s the ranking, beginning with a buy-and-hold item and ending something that you should get rid of tomorrow.

1. Depleted partnerships. Let’s say you buy Enterprise Products Partners (EPD) at $39 for the dividend. Over the next decade it pays out $15, but depreciation charges on the company’s pipelines shelter much of the distributions. And so (we will suppose for illustration) only $3 of your payout is taxable. The other $12 represents a nontaxable “return of capital.” That reduces your basis, or tax cost, from $39 to $27.

Now let’s say you sell, in 2024, at $44. You think you have a gain of only $5, but the IRS will have a harsher view. Your gain is $17. Of this, $5 will be taxed at the favorable rates for long-term capital gain. The other $12 is going to show up as a “recapture” of depreciation and get taxed at stiff ordinary-income rates.

So don’t sell your partnership shares. Hang on.

In 2024 you get run over by a cab on the Upper West Side. Your children inherit the EDP at its stepped- up value. If they sell, both the $10 of capital gain and the $25 of recapturable income are forgiven. If they keep the shares, their basis, which is a starting point for depreciation calculations, is $88. As a result, more of their dividends are sheltered than yours would have been if you had lived.

The taxation of partnerships is complex and sometimes counterintuitive. The important thing to know is that you should buy publicly traded partnerships only when you are in or near retirement, and you should cling to the shares. There is more on the tax theory here.

2. Collectibles. This category includes artwork, gold, and gold bullion funds (but not shares of gold mining companies). Long-term gains get taxed at a 28% rate, not the 15% or 20% rate that usually applies to stocks and bonds. So, other things (like the percentage gain in the asset) being equal, collectibles are things to keep and assets like stocks are things to sell.

3. Highly appreciated stock. If you are sitting on a ten-bagger, keep sitting on it if you can.

4. Roth money. Once you have paid the income tax on your IRA or 401(k), turning it into a Roth account, you and your heirs are home free for income taxes. Money compounds inside the account tax-free. Withdrawals are tax-free. You are under no obligation to withdraw from the account, and your heirs are entitled to the leisurely withdrawal schedule set out here.

All this makes a Roth a desirable asset. How desirable? That depends on your age, your heirs’ ages, your tax bracket and your tastes in investing. But in many cases you’d be better off dipping into a Roth for spending money than selling anything in categories 1 through 3 above.

Suppose you need to get your hands on $80,000 and your choice is between (a) selling Google shares that you bought long ago at ten cents on the dollar and (b) making an $80,000 withdrawal from the Roth account. If you are in a high tax bracket, option (a) might well compel you to sell $100,000 of shares in order to have $80,000 left after state and federal income taxes.

And let’s say you die not long after. Which would be more valuable to your heirs—$80,000 left in a Roth that would be sheltered from portfolio taxes, but not forever? Or a $100,000 stock position that could be reinvested in a diversified, tax-wise portfolio? For a lot of families, especially the ones that know how to minimize portfolio taxes, the $100,000 deal is the better one. Use option (b) to raise the $80,000.

5. Somewhat appreciated stock. Suppose you own Google shares that have merely doubled since you acquired them. They would be nice to have in an estate, but not as nice as a Roth account. Sell them before messing with that Roth.

6. Taxable IRAs. These are retirement accounts funded with previously untaxed contributions. The money might have come from deductible IRA contributions you made or from rollovers of pretax 401(k)s.

We’ll assume that you have already made any withdrawals from IRAs that you are compelled to make by dint of being 70-1/2 or older. The question is whether you pull out additional sums to cover bills. Sure, if you have exhausted assets in categories #8 and #9 below.

If you cash in a taxable IRA, you pay income tax on the money. If heirs cash it in, they pay. If you’re all in the same tax bracket, that’s a pretty much a tossup.

Except for one thing. Leaving the money in allows it to enjoy more years of tax-deferred compounding.

7. Bonds. If they have gone up at all since you bought them, it was probably only a little. These should be fairly close to the top of your sell list.

8. Cash.

9. Depreciated securities. If you bought a security for $30,000 that is now worth $18,000, sell it and claim a $12,000 capital loss deduction. Do this tomorrow. Do it even if you don’t need the cash.

You can get back into the same stock if you wait 31 days. If you are afraid the market will rebound while you are on the sidelines, use the loss-harvesting strategy described here.

Die with an underwater asset and the unrealized capital loss evaporates. This is the mirror image of the step-up rule. If assets are to get a step-up at death, then it’s fair they get a step-down, too.

You can use capital loss deductions to offset capital gains plus up to $3,000 a year of ordinary income. Unabsorbed losses are carried forward to future years. Absent gains, it will take you four years to put that $12,000 mistake to good use.

Alas, unused capital loss carryforwards suffer the same fate as unrealized capital losses when you die. They evaporate.

What if you bought the stock for $30,000, it’s now worth $18,000, and you are quite sure a $12,000 loss deduction will never do you a lick of good? (Example: You already have a giant loss carryforward and you are 90 years old.) Give the underwater stock to your granddaughter. She can’t claim your $12,000 loss, but in her hands the first $12,000 of price recovery is scot-free. She’ll have a taxable gain only to the extent she pockets more than $30,000.

Source: forbes.com

Recent Comments