The removal of a trustee from a trust can be a difficult and time consuming process for both beneficiaries and trustees alike. Courts are generally hate to interfere with a settlor/creator’s choice of trustees. However, most states provide trust beneficiaries a  judicial mechanism to remove a trustee when the relationship between beneficiaries and trustees has become intractable or the trustees have abused their authority to benefit themselves over the named beneficiaries.

judicial mechanism to remove a trustee when the relationship between beneficiaries and trustees has become intractable or the trustees have abused their authority to benefit themselves over the named beneficiaries.

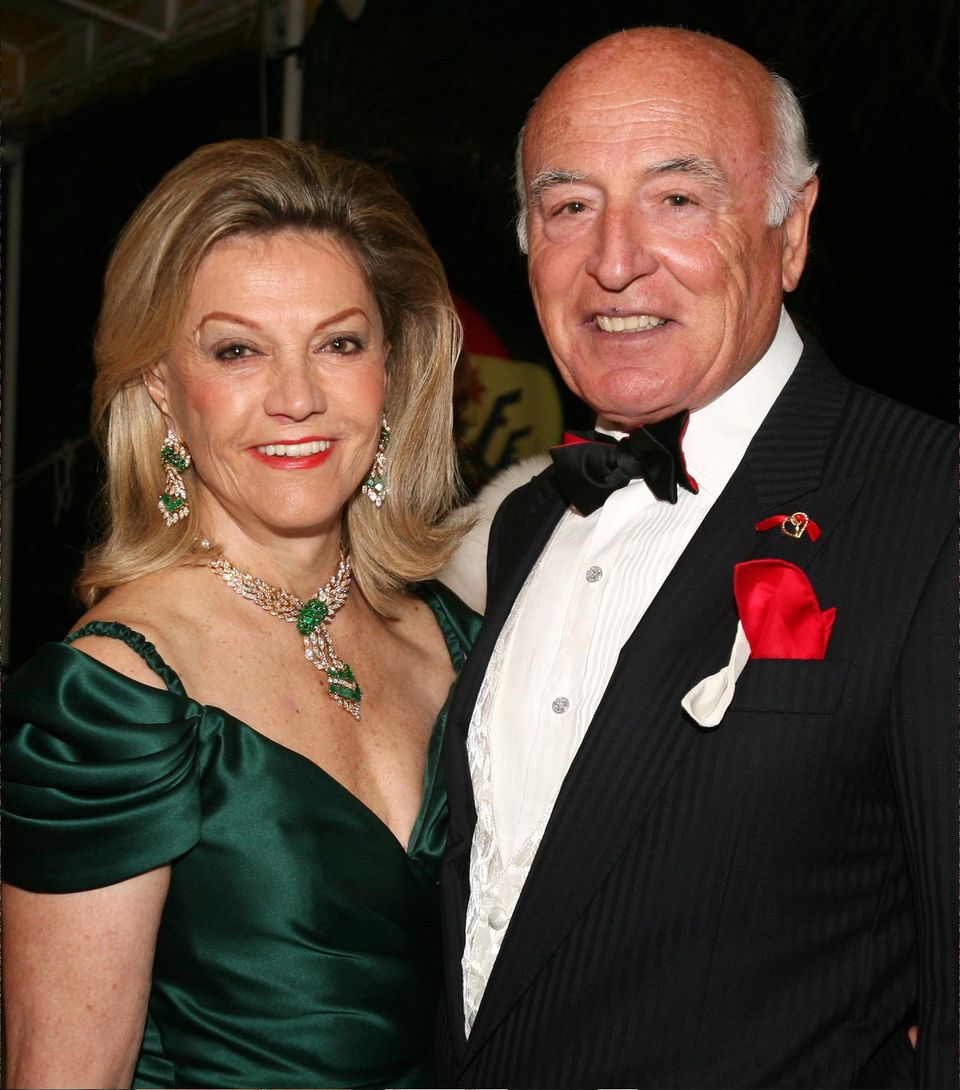

The Low-Carb King’s legacy is back in the news with a made-for-the-tabloids battle over his fortune. A recent removal proceeding in New York illustrates a typical example of a trustee/beneficiary relationship degenerating to the point where removal was granted.

Under New York Law, a trustee may be removed for wasting or improperly applying trust assets; improvidently managing or injuring trust property or for misconduct by the trustee in execution of his or her position. In this case, the widow of diet guru Dr. Robert C. Atkins sought the removal of three trustees who were managing the Marital Trust created by Dr. Atkins’ Will.

First, a lawsuit was filed in February, 2007 in state court in Miami, Fla., accusing Mr. Atkins’s widow, Veronica, of improperly firing the financial advisers who had been helping her manage her $400 million in assets. Ms. Atkins responded by filing a petition that April in New York City court, arguing that the advisers engaged in self-dealing and waste at her expense.

Ms. Atkins dubbed the advisors/trustees as the “Three Musketeers” stating they earned more than $8 million from Ms. Atkins since 2004. She claims they also purchased life insurance for her that would net them each $5 million if she met an early death.

Ms. Atkins recently married a Palm Beach socialite Alexis Mersentes who opposing lawyers call an “opportunist skilled in the art of seduction”. They are claiming that Mr. Mersentes tried to push them out and steal the Atkins fortune. Ms. Atkins and Mr. Mersentes say the “Musketeers” have fleeced a vulnerable widow and should be held accountable. Their suit called for the advisers to be removed as her trustees and seeks reimbursement of some of their fees.

The three trustees were not named in Dr. Atkins’ will, but succeeded the originally named trustees less than a year after letters of/for trusteeship were issued. Shortly after being appointed, the three trustees began to engage in a pattern of behavior that seemed to be directed more towards personally benefiting themselves than it did to serving the needs of Dr. Atkins’ widow, Veronica Atkins. This included the establishment of a separate LLC created by the three trustees which, through an agreement with Mrs. Atkins, paid the trustees monthly sums of no less than $100,000; having Mrs. Atkins waive her right to trustee commissions (as a co-trustee, she was entitled to a portion of the statutory commissions allowed in New York) and the naming of the three trustees as beneficiaries under Mrs. Atkins’ estate planning instruments.

It is no wonder that after several years, Mrs. Atkins became disenchanted with her co-trustees. She withheld payments under the agreement entered into by herself and the LLC owned by her co-trustees. This led to a breach of contract claim brought by the three trustees against Mrs. Atkins. This proved to be the final straw for Mrs. Atkins, and in 2007 she sought their removal in New York Court. She claimed that the three trustees were wasting trust assets and that the breach of contract suit was proof that she and her co-trustees had irreconcilable differences which could not be repaired.

As held by the Court, the overriding principle in deciding whether to remove a trustee is whether the trustee(s) whose removal is sought can continue to act in the best interests of the trust and whether the needs of the beneficiaries are being met. Trustee removal is a form of relief not routinely granted by the Court and only in the event that serious misconduct exists will the Court intervene. With regard to Mrs. Atkins, the Court held that it was clear that the relationship between the three trustees and Mrs. Atkins was beyond repair. Furthermore, it was also clear that the three trustees were looking out for their own interests and not the interests of Mrs. Atkins or the remainder of the Marital Trust.

The Atkins case poses a unique fact pattern which is not often present in many trustee/beneficiary disputes. First, the three trustees were not named in Dr. Atkins’ will and therefore, removing them would not be contrary to the trust creator’s wishes. Second, the actions taken by the three trustees were unequivocally done with their own self-interest in mind rather than the interests of Mrs. Atkins. In most trustee/beneficiary disputes, the disputed actions are not so black and white. Finally, the level of animosity between the three trustees and Mrs. Atkins had reached an intolerable level that would likely lead to further litigation and disputes if the three trustees were allowed to continue on as trustees.

Nevertheless, if a trustee/beneficiary relationship reaches the point where reconciliation or coexistence cannot be achieved, petitioning the court to remove a trustee may be the best available option to end the conflict and avoid wasting trust assets.